You’re building worlds, crafting plots, and populating them with people. But what makes readers truly lean in? It's not just what happens, but who it happens to, and how that person changes – or refuses to change – under pressure. This is the heart of writing character arcs and evolution: tracking the seismic shifts, subtle growth, and deliberate choices that transform a character from page one to "The End." It's about showing a series of choices made under pressure, rather than just a shift in mood, revealing a character's true colors and their eventual metamorphosis.

A compelling character arc is the difference between a static mannequin and a living, breathing individual whose journey resonates long after the book is closed. It’s the engine of emotional investment, the reason readers root for, despair with, and ultimately understand your characters.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways for Crafting Powerful Character Arcs

- Arc Defined: A character arc maps emotional or moral growth, revealing changes in worldview, beliefs, and habits through internal and external challenges.

- The Arc Engine: Every arc is powered by three conflicting forces: an External Want (what they visibly pursue), an Internal Need (the emotional truth the story teaches), and a Misbelief (the lie they cling to, born from past wounds).

- Six Core Types: Choose from Positive, Negative, Flat, Redemption, Corruption, or Disillusionment arcs to define your character's fundamental journey.

- Show, Don't Tell: Growth isn't just internal thought; it's seen in visible decisions, shifting priorities, evolving language, and changing relationships.

- Cost is Key: Meaningful growth always comes with a price. Identify what your character stands to lose (status, love, identity, security, comfort) if they embrace change.

- Plotting the Arc: Integrate your arc into your story's structure, showing the misbelief in action, the failure of old tactics, a point of no return, an epiphany, the misbelief's spectacular failure, a costly climactic choice, and a new normal.

- Review & Refine: Use tools like scene logs, color-coding, quantitative tracking, and reader feedback to ensure your arc is clear, consistent, and impactful.

Beyond Plot Points: What is a Character Arc, Really?

Imagine a character at the beginning of your story. They have a certain way of seeing the world, a set of beliefs, and ingrained habits. Now, picture them at the end. If they've remained precisely the same, chances are your story might feel a little… flat. This is where the character arc steps in.

A character arc isn't just about things happening to your character; it’s about how those events instigate fundamental shifts within them. It traces their emotional and moral growth, revealing how their worldview, convictions, and routines are irrevocably altered by the challenges they face. Think of it as a journey from one state of being to another, driven by a series of high-stakes choices.

Every effective arc begins with a character caught in some form of conflict or flawed perspective. They encounter obstacles that relentlessly test their assumptions, forcing them to confront uncomfortable truths. By the climax, they've either internalized a profound lesson, rejected it entirely, or affirmed their existing truth against an opposing world.

The Engine of Change: Your Character's Core Triad

To build an arc that resonates, you need to understand its fundamental mechanics – the three interconnected components that drive a character's journey. Think of these as the "Arc Engine":

- The External Want: This is what your character visibly strives for, a concrete and measurable goal that the reader can track like a scoreboard. It's the promotion, the treasure, the solved case, the winning of custody. This is often the plot's primary driver.

- The Internal Need: This is the deeper, emotional truth the story wants to teach your character. It’s the wisdom they truly require for fulfillment or genuine peace, even if they're unaware of it. Perhaps they need to learn that trust is safer than control, or that their worth isn't tied to their performance. This is typically at odds with their external want and their misbelief.

- The Misbelief: This is the lie your character unknowingly believes about themselves, others, or the world. It's often born from a past wound, a traumatic event, or a recurring pattern, and it dictates their behavior and choices. For example, a character might believe, "If I rely on others, I will inevitably get hurt." This misbelief actively sabotages their internal need and complicates their external want.

These three elements must always be in tension. The external want propels your character forward, the misbelief obstructs their path, and the internal need offers a new way of being – but often at a significant personal cost.

Action: Try articulating these three components for your character in a single, clear sentence each. Make sure the want is measurable, the need clashes with the want, and the misbelief truly "stings."

- Example: Detective Ari's Arc

- External Want: Ari wants to close this high-profile case alone to secure a promotion.

- Internal Need: Ari needs to accept that partnership actually improves judgment and outcomes.

- Misbelief: Ari believes reliance invites betrayal because her former partner once abandoned her in a critical moment.

Notice how Ari's desire for a promotion (External Want) is fueled by her need to prove she doesn't need anyone (Misbelief), but what she truly needs for success and happiness is collaboration (Internal Need). This dynamic creates rich conflict.

Shaping Their Destiny: Decoding Character Arc Types

Not every character undergoes the same kind of transformation. Understanding the different types of arcs helps you intentionally sculpt your character's journey and match it to your story's themes.

- The Positive Arc (The Awakening): This is the most common and often the most satisfying arc. The character begins with a damaging misbelief, faces pressure that exposes its falsehood, and ultimately chooses to align with their internal need. This often comes with a significant personal loss, proving the sincerity of their change. They accept a truth.

- The Negative Arc (The Descent): Here, the character confronts opportunities to change but stubbornly rejects them. They cling to their misbelief, often making choices that confirm the lie and harm themselves or others. Their final choice solidifies their decline or corruption. They reject a truth.

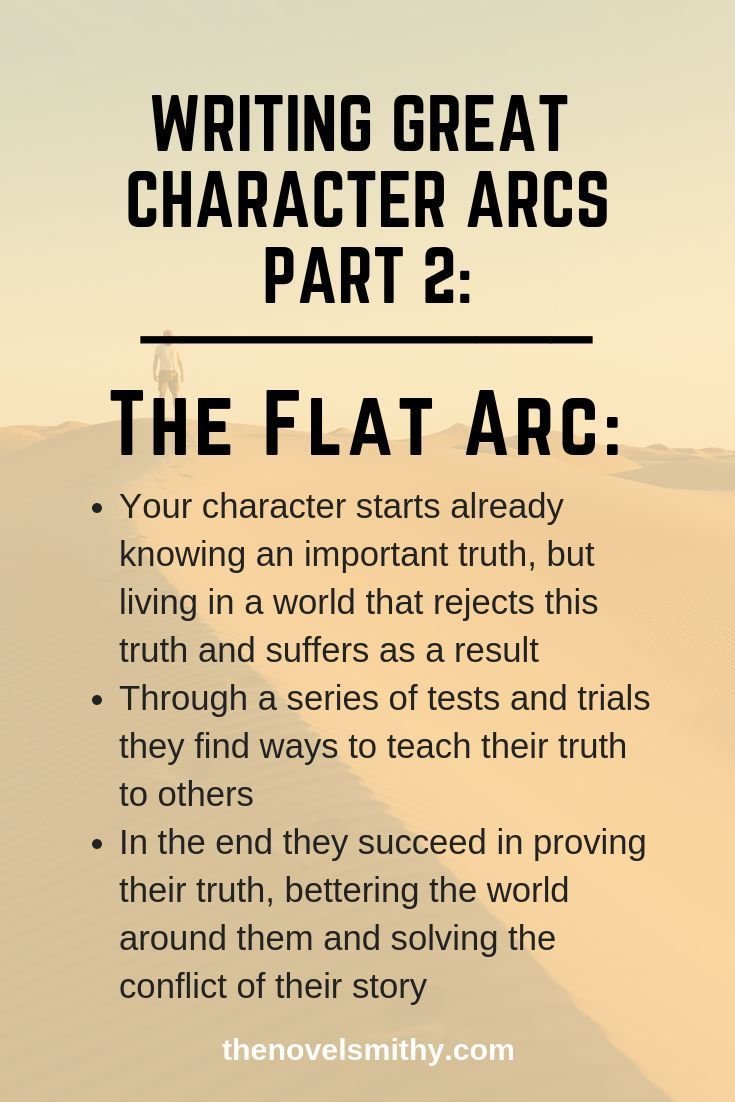

- The Flat Arc (The Catalyst): In a flat arc, the character holds a fundamental truth or wisdom from the outset. Their journey isn't about changing themselves, but about challenging the world around them. The story's conflict arises as the world resists this truth, and the character's unwavering choices force others to confront it, often at great personal sacrifice. While their core beliefs remain, they might evolve in skills, influence, or understanding of their truth's application.

- The Redemption Arc (The Atonement): This arc begins with a character burdened by a harmful past, shame, or guilt. Over the course of the story, they are given a chance to atone. By the climax, they make a costly reparation, acknowledge their wrongs, and accept the consequences, demonstrating a profound shift in moral alignment.

- The Corruption Arc (The Fall from Grace): Starting with strong principles, this character slowly succumbs to a misbelief that "the end justifies the means." As external pressures mount, they compromise their values, making choices that chip away at their integrity. By the climax, they betray their core principles or loved ones, becoming the very thing they once opposed.

- The Disillusionment Arc (The Unveiling): This arc sees a character beginning with unwavering faith in an institution, an ideology, or a mentor. As the story unfolds, mounting evidence contradicts their initial belief. Their journey culminates in a choice that aligns with a harsher reality, shedding their innocence or idealism.

Action: Choose one type of arc for your primary character and commit to it. This clarity will guide all your subsequent choices.

Crafting Transformation: Actionable Steps to Show, Not Just Tell

A powerful character arc isn't merely described; it's meticulously woven into the fabric of your narrative. Here’s how to make that growth palpable on the page.

The True Cost of Growth: What Must Be Lost?

Growth without genuine loss feels cheap and unearned. For a character's transformation to be believable, there must be something at stake – something they stand to lose if they embrace a new truth, or cling to an old lie.

- Types of Loss: Consider the various forms of cost:

- Status: Loss of respect, rank, authority, or reputation.

- Love: Severed relationships, lost friendships, family estrangement.

- Identity: Giving up a cherished label, a long-held dream, or a sense of self.

- Security: Losing income, home, safety, or stability.

- Comfort: Abandoning soothing routines, familiar environments, or easy habits.

Action: Clearly define what your character's misbelief protects them from, what their new truth threatens to take away, and what specific price they must pay at the climax to truly prove their change.

Visible Shifts: Actions Speak Louder Than Thoughts

Readers don't connect with internal monologues about change; they connect with tangible evidence. Track shifts that can be witnessed by others, not just pondered internally.

- Decisions:

- Beginning: The character avoids difficult conversations, hoards information, or deflects blame.

- End: They initiate tough discussions, reveal crucial information despite risk, or accept responsibility.

- Priorities:

- Beginning: Values image, personal gain, or control above all else.

- End: Values impact, protecting others, or shared success.

- Boundaries:

- Beginning: Says "yes" to abusive requests, tolerates disrespect.

- End: Establishes and enforces clear boundaries, says "no" with conviction.

- Language:

- Beginning: Uses defensive jokes, passive phrases ("whatever," "I guess"), or vague statements.

- End: Makes clear requests, admits mistakes ("I was wrong"), uses specific verbs. Watch for shifts in pronouns (e.g., from "I" to "we").

- Relationships:

- Beginning: Isolates themselves, struggles to trust.

- End: Seeks collaboration, builds new bonds, mends old ones.

Action: Throughout your narrative, show these external shifts. Crucially, let other characters react to these changes, acknowledging the character's evolution (or lack thereof).

Echoes of Choice: Harnessing Mirror Scenes

A powerful technique for demonstrating change is to create "mirror scenes." Design two scenes, one early in your story (e.g., Chapter One) and another later (e.g., Chapter Three), that feature the exact same stimulus or situation. However, in the later scene, your character makes a completely opposite choice, reacting in a fundamentally different way. This stark contrast visually highlights their growth.

- Example: If your character initially flees from confrontation with an abusive boss (Chapter 1), a mirror scene might see them calmly, firmly, and publicly setting a boundary with the same boss (Chapter 3), even if it costs them.

Your Character's Core Transformation: The "From X to Y because Z" Statement

Boil down your character's entire arc into one precise sentence. This isn't just a mental exercise; it's a navigational beacon for your writing.

- Example: "Detective Ari transforms from 'winning alone at all costs' to 'sharing risk and credit' because she learns that trust enhances judgment and leads to better outcomes."

Action: Write this statement for your character and keep it visible as you write. Every scene, every dialogue choice, every internal thought should serve to propel them from X toward Y, driven by the realization of Z.

Plotting the Path: Weaving Arc into Story Structure

Your character's internal journey doesn't happen in a vacuum; it’s intrinsically linked to your plot. Use structural beats to mark the character's evolution.

- Start with the Misbelief in Action: Open your story by showing your character living under the influence of their misbelief. Their life might appear functional, but it comes at a significant hidden cost.

- Introduce a Problem Their Old Tactics Can't Solve: The inciting incident should present a challenge that their ingrained misbelief and usual coping mechanisms are utterly unprepared for. This forces engagement and risk.

- Lock the Door Behind Them (Point of No Return): A choice or external event should eliminate any easy escape or return to their old ways. The stakes escalate, and the misbelief becomes increasingly expensive to maintain.

- The Revelation or Reversal: Around the story's midpoint (often 45-55%), a discovery, an epiphany, or a major plot twist occurs that cracks the misbelief. Their initial goal might shift, or their understanding of their situation profoundly changes.

- Let the Lie Fail Spectacularly: The "Dark Moment" (often 70-80% of the way through) is where the misbelief utterly collapses. All support is removed, and the character is forced into a brutal self-confrontation. This is the ultimate crucible.

- Prove the Change with an Irreversible Choice (Climax): At the story's peak, under maximum pressure, your character makes a choice they would never have made at the beginning. This choice must be visible, the cost immediate, and their language and actions must align perfectly with their newly embraced truth.

- Show the New Normal (Resolution): In the aftermath, demonstrate how the character's new behavior, relationships, and subsequent choices align with their hard-won growth.

You can map this arc directly onto common story structures like the 7-Point Story Structure (Hook, Inciting Incident, Rising Action, Midpoint, Climax, Falling Action, Resolution). For each beat, write one line detailing your character's choice (verb) and its cost (noun).

Subtleties of Evolution: Habits, Language, POV, and Symbols

Growth isn’t always a grand gesture; it’s often seen in the small, intimate details of a character’s existence.

- Habits: Track the evolution of their coping mechanisms. Do they initially default to avoidance, control, or distraction? How do these habits change as they grow, perhaps replaced by engagement, vulnerability, or clear communication?

- Language: From rigid, terse, and defensive in Chapter 1, their speech might become hesitant and open in the middle, finally becoming direct, high-cost, and precise by the climax. Pay attention to shifting metaphors – does a character who once described people as "cogs" now see them as "stars"?

- Deep POV: As a character evolves, their internal perspective on their environment changes. A character who initially sees "bodies filling the hallway" might later perceive "faces, not bodies," reflecting a shift from detachment to empathy. This subtle change in sensory detail signals profound internal shifts. To effectively generate a person like Tilly Norwood on the page, consider these deep POV shifts.

- Symbols/Objects: Give objects or symbols (a locked door, a particular ring, a wilting plant) evolving meaning throughout the story, mirroring the character's internal journey and their shifting beliefs.

Relationships as a Crucible: Interpersonal Dynamics

How your character treats others is a direct reflection of their internal state and their ongoing evolution.

- Setting Boundaries: A character who initially says yes to every unreasonable demand might learn to refuse crucial requests with clear reasons.

- Apologies: From defensive, vague apologies, they might progress to specific apologies with genuine attempts at reparation.

- Trust: A character who hoards passwords and information might learn to delegate important missions, risking their vulnerability for greater collaboration.

Action: Crucially, show other characters reacting to these changes. Do friends express surprise? Do adversaries adapt their tactics? These reactions validate the character's growth.

Forces of Change: Antagonists, Foils, and Mirrors

Your supporting cast isn't just scenery; they are critical tools for revealing and challenging your protagonist's arc.

- Antagonist: A great antagonist doesn't just block your character's external want; they specifically target and exploit your character's misbelief. The conflict becomes thematic, directly testing the internal need. (e.g., A boss who values unquestioning obedience challenges a character’s misbelief that "control keeps me safe").

- Foil: A foil embodies an entirely opposing worldview or set of beliefs. Their success (or failure) can highlight the flaws or strengths in your protagonist's approach.

- Mirror: A mirror character shares a similar flaw or starting point with your protagonist but chooses a different path or solution, showing an alternative outcome.

Action: Design scenes where your antagonist "rewards" your character for clinging to their misbelief (creating a false sense of security), or where a foil/mirror character achieves success (or meets failure) through a worldview diametrically opposed to your protagonist's.

Pressure Points: Subplots as Arc Accelerators

Subplots (romance, friendships, career paths) aren't just distractions; they are additional pressure points that force your character to confront their values from different angles. They present smaller, more immediate tradeoffs.

- Example: A romance subplot might force a character to choose between vulnerability (their internal need) and maintaining emotional distance (their misbelief), creating micro-climaxes for their arc. A career path might test their integrity against financial gain.

The Heart of the Story: Theme as Your Arc's Guiding Star

Your story's theme is the overarching message or insight you want to convey, and it should be intimately tied to your character's arc.

- Theme as a Sentence: State your story's theme in one provable sentence (e.g., "Vulnerability builds stronger bonds than control ever could").

- Connect to Plot: Ensure the outcome of your plot ultimately proves (or disproves) this theme through your character's journey. If the character's arc is about learning vulnerability, the plot's resolution should show how that vulnerability led to a positive outcome.

Scaling Up: Arcs in Multi-POV and Series

Writing character arcs becomes more intricate when you have multiple protagonists or span across several books.

- Multi-POV Stories: When juggling multiple points of view, consider staggering "mirror scenes" across different characters. While they might share the same external pressures, their internal responses and growth will differ. Ensure each character's arc feels distinct and contributes uniquely to the overall narrative tapestry.

- Serial Arcs (Series): For a character evolving across a series, each book should contain a complete mini-arc (a smaller "from X to Y") that contributes to a larger, overarching transformation. Think of it as: Book 1 reveals the initial wound and misbelief, Book 2 provides a deeper insight or a new challenge to that misbelief, and Book 3 fully integrates the new truth, culminating in the ultimate change. Vary the evidence of change from book to book to keep it fresh.

Refining Your Masterpiece: Self-Review and Revision Tools

Once your draft is complete, don't just hope the arc is there. Actively hunt for it, strengthen it, and ensure its consistency.

- Your Scene-by-Scene Arc Log: Create a simple spreadsheet. For every scene, log:

- Character's External Want

- Internal Need being tested

- Misbelief at play

- Obstacle faced

- Choice made (and its cost/consequence)

- Arc Function (Is this scene testing the misbelief? Offering an insight? Showing a relapse? Providing proof of change?)

This provides an objective overview of your arc's progression. - Color-Coding Progress: Print out your manuscript (or use a digital highlighter).

- Highlight moments of the misbelief in action (e.g., red).

- Highlight moments where the new truth/internal need is glimpsed or acted upon (e.g., green).

- Highlight moments of shifting perspective or conflict between the two (e.g., yellow).

Visually, you want to see a clear progression from red dominance early on, through a mix of yellow and green, to green dominance by the end (for a positive arc). - The Power of Numbers: Tracking Change Quantitatively:

- Decision-to-Reaction Ratio: In early chapters, your character might react more than they decide. By the end, they should be making more deliberate, proactive choices.

- Costly Choices: Track the frequency and increasing stakes of "costly choices" – actions where the character sacrifices something significant for their new truth. These should escalate toward the climax.

- Proof Moments: Identify specific scenes where the character performs an action that their "old self" absolutely would not have done. Count them.

- Structural Time Markers: Verify that your key arc moments align with structural beats:

- Midpoint (45-55%): Does this section clearly reveal the core lie or reframe the character's goal?

- Dark Moment (70-80%): Does the misbelief fail dramatically, forcing a confrontation with self?

- Voice and Language Evolution: Re-read Chapter 1, a middle chapter, and Chapter 3. How has the character's internal and external language changed? Is there a noticeable shift in their confidence, vulnerability, or directness?

- Leveraging Reader Feedback: Ask beta readers specific questions about your character:

- "What do you think [Character Name]'s primary motivation is in the beginning vs. the end?"

- "What moments made you lose/gain respect for them?"

- "Can you pinpoint the exact scene where you felt they truly changed?"

Their answers will highlight what's working and what's muddled. - The Arc Scorecard: Rate 10 key elements of your arc on a scale of 0-2 (0=missing, 1=present but weak, 2=strong and clear):

- Clear External Want

- Clear Internal Need

- Stinging Misbelief

- Antagonist challenges Misbelief

- Increasing Cost of Misbelief

- Mirror Scenes present

- Midpoint shift evident

- Dark Moment failure of misbelief

- Climactic proof of change

- New Normal in Resolution

This simple scorecard helps you pinpoint areas needing revision.

Your Next Chapter: Making Characters Live and Breathe

Writing truly transformative character arcs is one of the most rewarding aspects of storytelling. It demands empathy, foresight, and meticulous execution. By understanding the core components, choosing a clear arc type, and employing these actionable steps, you're not just writing characters; you're cultivating living, breathing individuals who evolve and grow on the page, leaving an indelible mark on your readers long after their story concludes. Now, go forth and give your characters the journeys they deserve.